Joel and

Ethan Coen’s Fargo opens,

appropriately, in Fargo, North Dakota, although this is the only scene in the

movie to actually take place in the title location. Over the opening credits we

see a car, barely visible through the fog in the distance as it makes its slow

progression through the snowy, bluish gray landscape. The tan Sierra goes up

and down on the frozen-over roads, occasionally disappearing into snowy voids.

The Coens’ Midwest is bleak and ominous, a mood perfectly underlined by Carter

Burwell’s gloomy score. The brothers and virtuoso director of photography and

long-time collaborator Roger Deakins create an epic landscape of near mythical

proportions, if only for the purpose of contrasting it with the ordinariness

and decidedly unheroic nature of the characters that inhabit it. Contradictions

like this one abound in the Coens’ universe; their work has always defied

definition. They play fast and loose in terms of plot and refuse to be

constrained by the formal imperatives of conventional narrative, stitching

together a number of different genres and in the end transcending such

conventions altogether. Fargo starts

out as a perfect-crime drama, but soon embraces conventions of the noir, the

thriller, and tragedy, all with a big, darkly humorous smile on its lips.

Intro

I love movies. I have loved movies all my life. I grew up on them. When I was eight years old, I managed to convince myself I would make movies when I grew up. Now I am in the process of getting a degree in Film Studies. I write about film more than ever before, partly because I have to for my classes, mostly because I enjoy it, because I have something to write about. Sometimes it helps me understand the film better; sometimes it helps me understand myself better.I created this blog as a place to showcase my work, and also as an incentive to keep writing reviews, analyses, and essays over breaks, when there’s no one here to grade me.I have tried many times, and failed, to explain in a coherent manner why it is that I love films. Here is my best—and most coherent—guess.

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

Saturday, November 23, 2013

Sennett and Roach: Two Methods to the Madness

“The Mack Sennett Keystone comedies were the culmination of

15 years of comic primitivism—the characterless jest and the excitement of

motion raised to the nth power” (Mast 43). Before Sennett, American film comedy

had been confined to the music hall sketch; he gave it the freedom of

destructive absurdity. While still

at Biograph, the future King of Comedy moved Griffith’s static, inert,

indoor-bound camera outside, where it enjoyed both visual freedom and the

freedom to move. And move it did, at mad speed, nearing supersonic velocity,

stopping only when the figures onscreen smashed through one wall too many, fell

down manholes or wells too deep, or were simply overcome with exhaustion The

filmmaker added tremendous energy and breathtaking pace, the incongruous and

the non sequitur, and a taste for burlesquing people, social custom, and the

conventions of other films.

“The Mack Sennett Keystone comedies were the culmination of

15 years of comic primitivism—the characterless jest and the excitement of

motion raised to the nth power” (Mast 43). Before Sennett, American film comedy

had been confined to the music hall sketch; he gave it the freedom of

destructive absurdity. While still

at Biograph, the future King of Comedy moved Griffith’s static, inert,

indoor-bound camera outside, where it enjoyed both visual freedom and the

freedom to move. And move it did, at mad speed, nearing supersonic velocity,

stopping only when the figures onscreen smashed through one wall too many, fell

down manholes or wells too deep, or were simply overcome with exhaustion The

filmmaker added tremendous energy and breathtaking pace, the incongruous and

the non sequitur, and a taste for burlesquing people, social custom, and the

conventions of other films.

Hal Roach was always second to Sennett; the latter

established the formula while the former merely adopted it. While Roach began

imitatively, copying Sennett’s chases, falls, custard-pie throwing, and

generalized chaos, he gradually began thinking more in terms of character than

non sequitur, carefully structured gags instead of speed, logical plotting

rather than constant, cumulative romping. Roach’s films benefited from more

structure, less improvisation, creating what Gerald Mast calls a perfect

stairway to insanity (185). To use the same metaphor, Sennett did not ever take

the stairs up; he took the elevator, punched the floor button—or, if feeling

especially inventive, whacked it with a hammer—got stuck a couple of times

between levels, sometimes plummeted, coming close to the bottom of the elevator

shaft, and, finally, shot through the roof.

Sunday, November 10, 2013

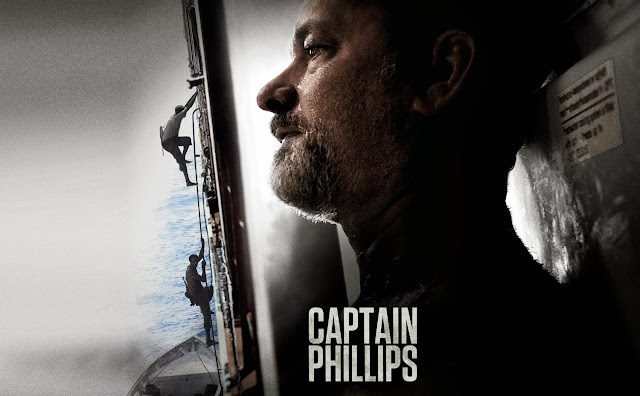

Captain Phillips (2013)

Sandwiched

in between Gravity and All Is Lost, Paul Greengrass’ Captain Phillips is only one of many,

incredibly well-made, gripping but grim survival tales to hit the theaters this fall—a season of soaring cinematic standards as much as of falling leaves.

Impeccably

constructed and surprisingly complex, the movie succeeds on all notes but one:

characterization. Based on the real-life takeover of an American cargo ship by

Somali pirates, it offers an immaculate reconstruction of a chaotic incident,

portrayed on screen with immediacy and intelligence. Full of kinetic energy,

exciting and suspenseful, the film traces Captain Richard Phillips’ ill-fated

journey on and off the Maersk Alabama in early April of 2009. The only problem

is we don’t know enough about him, the journey, the ship, or the pirates to

care.

“It’s just

business,” pirate leader Muse (Barkhad Abdi) keeps repeating, a phrase not

actuality uttered, but reflected in the attitude of Captain Phillips

(Tom Hanks, portraying the kind of quiet, commanding role Oscar dreams are made

of). Curt and professional towards his crew and extremely attentive to security

measures, the title character is a civilian tasked with getting a huge cargo

ship safely from Oman to Kenya down the Horn of Africa. It’s clear he just

wants to get the job done as quickly and effectively as possible.

Friday, November 1, 2013

The Counselor (2013)

The Counselor, Cormac McCarthy’s much-anticipated screen-writing

debut paints an elusive, eccentric, exquisitely rendered picture of poetic

pain. Filled with bizarre, bone-grinding violence, twisted characters,

confusion and moral compromise, Ridley Scott’s movie becomes a sodden, sordid

cautionary tale of good and—mostly—evil. If you were looking forward to the

crime thriller—more Tony

than Ridley—the film’s trailer

seems bent on promoting, The Counselor

is not it.

Michael Fassbender heads a burning hot all-star cast, all outshined,

hover, by the pulpy, lyrical, hardboiled and hell-bound script, a foray into

the mesmerizing and merciless milieu of corrosive drug trade on the

American-Mexican border—a barrier as moral as it is geographical for much of

American fiction. McCarthy and Scott enter a closed, dangerous, elite world,

devoid of any ordinary people to act as gateways or guides for the audience or

to remind us of a reality beyond the brutal one of the cartel.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)