Sandwiched

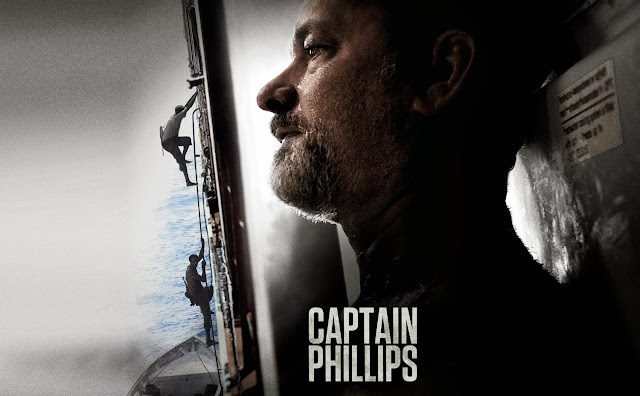

in between Gravity and All Is Lost, Paul Greengrass’ Captain Phillips is only one of many,

incredibly well-made, gripping but grim survival tales to hit the theaters this fall—a season of soaring cinematic standards as much as of falling leaves.

Impeccably

constructed and surprisingly complex, the movie succeeds on all notes but one:

characterization. Based on the real-life takeover of an American cargo ship by

Somali pirates, it offers an immaculate reconstruction of a chaotic incident,

portrayed on screen with immediacy and intelligence. Full of kinetic energy,

exciting and suspenseful, the film traces Captain Richard Phillips’ ill-fated

journey on and off the Maersk Alabama in early April of 2009. The only problem

is we don’t know enough about him, the journey, the ship, or the pirates to

care.

“It’s just

business,” pirate leader Muse (Barkhad Abdi) keeps repeating, a phrase not

actuality uttered, but reflected in the attitude of Captain Phillips

(Tom Hanks, portraying the kind of quiet, commanding role Oscar dreams are made

of). Curt and professional towards his crew and extremely attentive to security

measures, the title character is a civilian tasked with getting a huge cargo

ship safely from Oman to Kenya down the Horn of Africa. It’s clear he just

wants to get the job done as quickly and effectively as possible.

The story

evolves against a volatile political backdrop the kind Greengrass has shown a

preference for (Bloody Sunday and United 93 complete the director’s loose

trilogy of average individuals caught in the throes of politically motivated

violence). The quintessential Everyman soon to be facing extraordinary

circumstances, Phillips is fully aware his ship looks much like a floating

jackpot; he compulsively checks unlocked gates and runs his crew through

security drills.

The story

evolves against a volatile political backdrop the kind Greengrass has shown a

preference for (Bloody Sunday and United 93 complete the director’s loose

trilogy of average individuals caught in the throes of politically motivated

violence). The quintessential Everyman soon to be facing extraordinary

circumstances, Phillips is fully aware his ship looks much like a floating

jackpot; he compulsively checks unlocked gates and runs his crew through

security drills.

The story

evolves against a volatile political backdrop the kind Greengrass has shown a

preference for (Bloody Sunday and United 93 complete the director’s loose

trilogy of average individuals caught in the throes of politically motivated

violence). The quintessential Everyman soon to be facing extraordinary

circumstances, Phillips is fully aware his ship looks much like a floating

jackpot; he compulsively checks unlocked gates and runs his crew through

security drills.

The story

evolves against a volatile political backdrop the kind Greengrass has shown a

preference for (Bloody Sunday and United 93 complete the director’s loose

trilogy of average individuals caught in the throes of politically motivated

violence). The quintessential Everyman soon to be facing extraordinary

circumstances, Phillips is fully aware his ship looks much like a floating

jackpot; he compulsively checks unlocked gates and runs his crew through

security drills.

Meanwhile,

on the beach of the pirate city of Eyl, Somalia, shouting, rifle-toting African

men are organizing quite a different voyage out to sea, one intended to hijack

vessels and bring back money and Western hostages who might be exchanged for

very large ransoms. As my college politics professor told our class, these

pirates don’t say “arrrrgh,” they say, “give me your money or I’ll shoot you in

the fucking face.”

A

smorgasbord of diverse settings, languages and accents, technologies high and

low, and constant movement from one place to another grab hold of you from

these very first scenes, an elegant and economical exposition handled

gracefully by Greengrass and cinematographer Barry Ackroyd.

Presenting

the hulking, graceless container ship plod along the high seas and comparing

its size to the Somalis’ small, ill-equipped skiffs, hardly more than specks on

the horizon, Greengrass captures, in one image, the essence of the conflict. Captain Phillips, without an ounce of

didacticism, deepens, brilliantly and unexpectedly, into an unsettling look at

global capitalism and American privilege and power.

Although the

filmmaker pits African locals against Americans, boiling down to a finale that

involves Navy SEALs, U.S. choppers and warships, he focuses on the reality of

impoverished young men pushed to extreme, agonizing measures instead of

vilifying the pirates. Phillips is undoubtedly the hero we’re supposed to root

for, but the movie steadily, almost stealthily, asserts the humanity of his

captors, untrained and malnourished villagers with gaunt, angular faces,

stained teeth and wild eyes. “I have bosses,” one of the pirates explains of

their demands, as if he were an intern ordering a coffee for his supervisor.

Although the

filmmaker pits African locals against Americans, boiling down to a finale that

involves Navy SEALs, U.S. choppers and warships, he focuses on the reality of

impoverished young men pushed to extreme, agonizing measures instead of

vilifying the pirates. Phillips is undoubtedly the hero we’re supposed to root

for, but the movie steadily, almost stealthily, asserts the humanity of his

captors, untrained and malnourished villagers with gaunt, angular faces,

stained teeth and wild eyes. “I have bosses,” one of the pirates explains of

their demands, as if he were an intern ordering a coffee for his supervisor.

Nothing more

than a low-ranking functionary in a vast piracy hierarchy, Muse attacks the

opportunity to take over Phillips’ ship with the hungry intensity of a man who

has been oppressed and now has a chance to play the oppressor. “Look at me,” he

tells Phillips, staring steadily into his eyes. “Look at me. I’m the captain

now.” The pirate establishes a measure of rapport with Phillips, a silent

understanding of each other’s plans, priorities, strengths and weaknesses. The

standoffs between Hanks and Abdi bristle with quiet electricity, although Greengrass

affords little three-dimensionality to the other pirates, including hothead

Najee (Faysal Ahmed) and scared teenager Bilal (Barkhad Abdirahman).

The first,

and best, half of the movie is devoted to the captain’s clever attempts to protect

his men. In a suspenseful, carefully choreographed cat-and-mouse game, Phillips

tries to stall for time as the crew hides in the engine room. Hanks excels at

showing us exactly what’s racing in his character’s mind while maintaining an

almost ridiculously calm and friendly façade. A detached, plain-spoken

taskmaster, Phillips is forced by script and circumstance to thrust himself

into the mold of self-sacrificing hero.

Around the

midpoint of the movie, the pirates escape with $30,000, all the money in the

cargo ship’s safe, and their most valuable asset, Captain Phillips, in an ugly,

orange lifeboat in which tension, temperature and tempers will escalate.

Greengrass collapses the comparative expansiveness of space on the ship into a

crucible of claustrophobic chaos, a cramped floating coffin.

The film’s

finale might be the saddest happy ending I’ve ever seen. Big men with big guns

do their job—isn’t that what everyone in the film is trying to do?—but the victory

feels hollow, leaving you in a state of dread and anxiety rather than

excitement, not unlike the perfectly, purposefully anti-climactic ending of

Kathryn Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty. Even

more powerful than Captain Phillips’

rescue mission itself is Hanks’ stunned response and the emotional aftermath,

which dismantles every notion of macho Hollywood heroism. The shattering rendering

of shock is unique and extraordinary in its subtlety, simplicity and wordless

silence. The attending nurse offers Phillips routine reassurances, just doing

her job as best she can, which was every character’s purpose. The world has

gone back to normal; Captain Phillips has not.

Aided by the

racing camerawork, Henry Jackman’s throbbing electronic score and the

crackerjack editing by longtime collaborator Christopher Rouse, the film rips

along without relinquishing its grip. Its greatest asset, however, might be its

biggest weakness. Captain Phillips’ irreproachable

style shakes you up more than its story.

The captain

is first seen in a postcard-perfect white Vermont home and then sharing

concerns for his children’s futures and a fast, scarily changing world in

general with his wife (Catherine Keener). The sole purpose of this slightly

awkward, gratuitous scene is to underscore the character’s decency, humanity

and vulnerability. That it succeeds at all is a testament to the actors’

likeability more than anything else, and no other attempt is made to endear Phillips

to the audience. His actions throughout the film are noble and brave,

demonstrating a deeply ingrained sense of honor and duty that go beyond any

sense of responsibility or obligation. If that sounds at all familiar, it’s

because his character is never developed past the point of the principled,

upright guy of countless movies past.

Hanks is an

actor with an innate ability—unequaled by any of his contemporaries— to convey

a sense of old-fashioned American decency just by his presence in the frame.

But is that presence enough to make us care whether Phillips lives or dies? The

audience cares about him out of a sense akin to the character’s own dutiful

behavior—because caring seems like the right, honorable thing to do, not

because there is any reason behind it. Connecting to an onscreen character

should not be a matter of obligation for viewers.

No comments:

Post a Comment